Enhancing LLM Reasoning with Agentic Systems

How structure helps enhance reasoning capabilities

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized how we interact with information. They are incredibly good at generative tasks: writing emails, summarizing documents, or writing code. They are also very powerful at extracting information from documents, e.g., answering user questions about the content of a file, making them a very efficient assistant for many reading-intensive tasks.

Within the context of decision-making, analyzing information and relating those data points to specific tasks is a key component. However, a crucial and very different capability necessary for a tool to support decision-making is the ability to reason: thinking about something in a logical, sensible way.

Reasoning requires multi-step planning, adhering to constraints, performing accurate calculations, and maintaining an overall consistent chain of logic over time. When we directly ask an LLM to solve a difficult problem or make a complex decision using a single prompt, we often encounter recurring issues: subtle inaccuracies, logical disconnects, or outright hallucinations.

The "State Management" Problem

At their core, LLMs are "stateless" next-token prediction machines. They don't "think" in the human sense; they predict the most likely continuation of the text they currently see in their context window. When dealing with complex tasks, it is often helpful to break down the initial problem into smaller pieces and follow logical steps to come to the final solution.

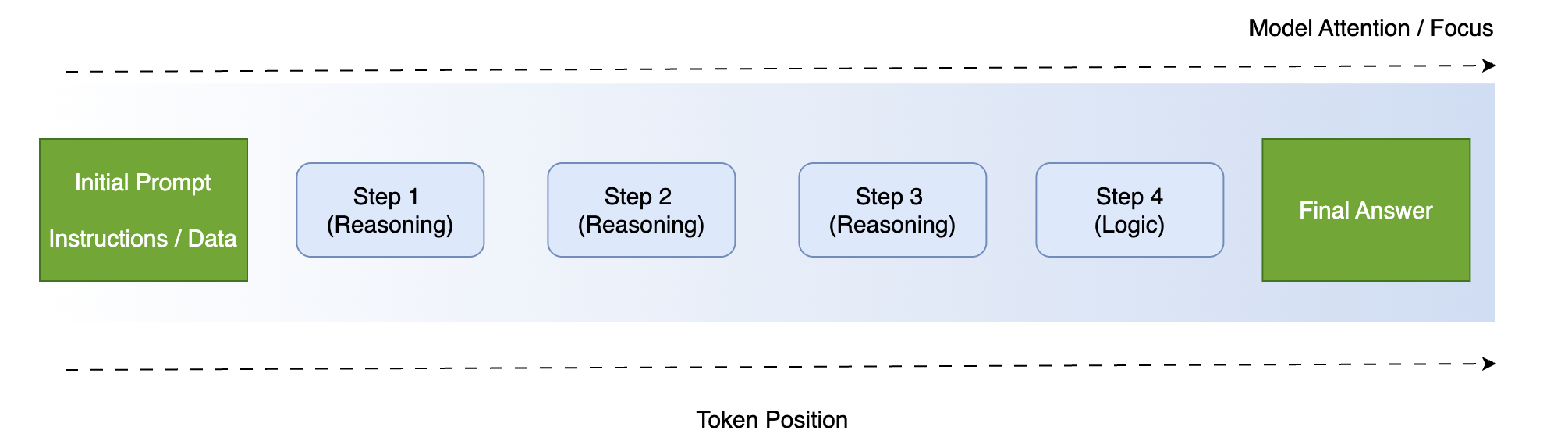

Figure 1: Context Window Illustration and Attention Decay

Doing so requires the ability to keep track of a logical chain of steps, or “states,” which is very difficult to do without an explicit dedicated mechanism. Imagine trying to solve a complex calculus problem without taking notes on paper. You would have to hold every intermediate number and step in your immediate “working memory.” Eventually, your brain gets overwhelmed, you drop a variable, and the final answer is wrong.

Similarly, if you give a complex “one-shot” prompt to an LLM, its "working memory" (the context window) gets flooded with intermediate steps, noise, and instructions. Eventually, it begins to "forget" context or hallucinate details it can no longer track.

Evolving Architectures and Prompting

Recently, researchers have come up with different ways of improving the quality of reasoning of LLMs. Two interesting approaches revolve around either changing the prompt fed to the LLM to force it to follow specific steps, or to give it a better framework for solving a specific problem.

1. Chain of Thought (CoT) Prompting

The first major breakthrough was realizing that if you force the LLM to "show its work," it performs better. Chain of Thought (CoT) involves prompting the model to think step-by-step before giving a final answer. By generating the intermediate steps into its own context window, the LLM effectively creates its own "scratchpad," helping it stay on track longer. However, it still relies entirely on the LLM's internal state and remains highly sensitive to the prompt; changing a single word in the instructions can lead to vastly different reasoning paths.

2. Agentic Systems

An agentic system is a coordinated framework of individual components designed to solve a complex problem. Rather than relying on a single model, this architecture integrates multiple elements, including specialized LLMs, deterministic code, or external APIs, to function as a unified system. By building a modular system, one can effectively separate specific functionalities: one agent solves a narrow piece of the problem, while the critical "state management" is handled externally by a structured database or a deterministic logic loop.

Experiment: Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

To highlight the reasoning capabilities of different approaches, we utilized a classic optimization problem: the Traveling Salesman Problem. The objective is to identify the shortest route visiting N cities exactly once. For this experiment, N=15 and the optimal cost is 291. Solving this requires the ability to satisfy simple constraints while keeping track of candidates and their cost during the search for a solution. We conducted this experiment using the Amazon Nova Premier model, one of the most advanced models for dealing with complex tasks.

Scenario A: "Zero-Shot" Attempt

A baseline scenario where we provided the LLM with the full distance matrix and a direct instruction to solve the problem in a single pass.

Prompt:

Solve the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) for this Distance Matrix.

Format: Return ONLY the path (e.g., [0, 5, 2...]) and the total cost.

Distance Matrix: {matrix}Scenario B: Chain of Thought (CoT)

We guided the model to use the Branch and Bound Algorithm, instructing it to explicitly follow a detailed step-by-step process.

Prompt:

You are an expert mathematician solving the Traveling Salesman Problem.

Your goal is to find a valid, low-cost path visiting all cities exactly once.

**Strategy: Step-by-Step Instruction for Branch and Bound Algorithm**

{step by step guide}

**Format your answer exactly like this:**

<Example Step 1>

...

Final Verification:

- Path: [0, 12, ..., 0]

- Total Calculation: 23 + ... = TOTALScenario C: The Agentic System

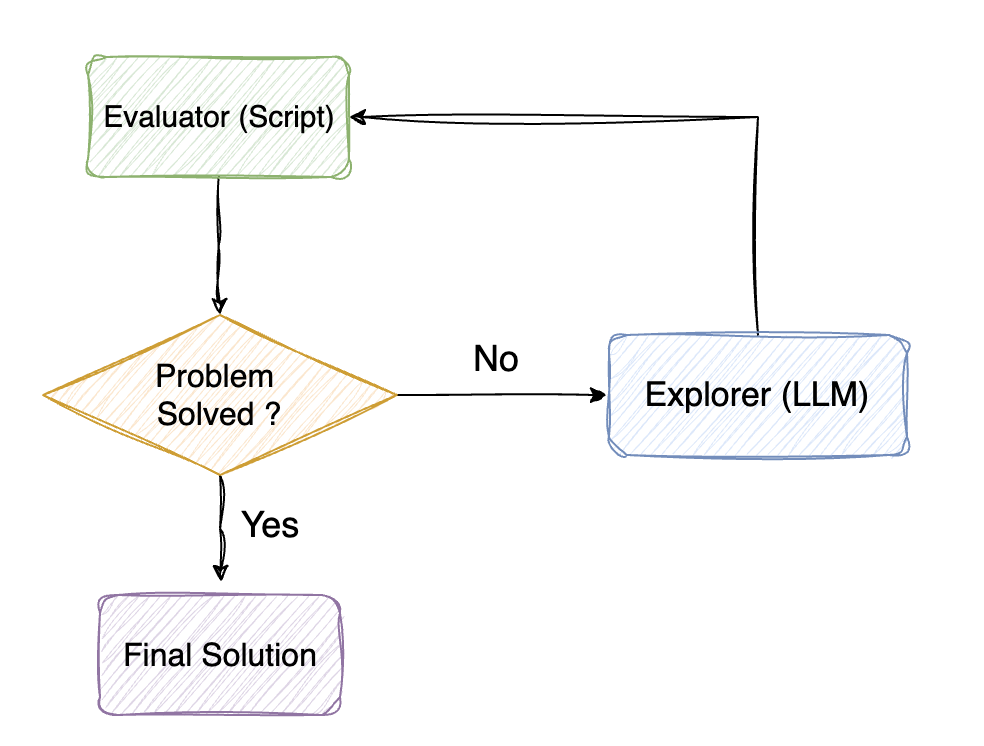

We move away from a single-prompt interface to a modular system. This architecture consists of two specialized components coordinated via an external state.

Figure 2: Simple Agentic System

The Exploration Engine (LLM)

The LLM acts as the exploration engine of the search. At each iteration, it is provided with the current status of the optimization, including cumulative costs and path depths. Its role is to analyze available partial solutions and strategically select the most promising branches to explore next.

The Compute & State Management Engine (Deterministic Tool)

This script handles the evaluation and state management part of the search. It manages the current search state and update costs, allowing the LLM to focus on exploration without needing to remember numerical details.

Stopping Criteria

The system continues its loop until the agent decides that the optimal solution has been reached or the maximum number of iterations has been reached.

Results

| Metric | Zero-Shot | CoT Prompt | Agentic System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Found Feasible Solution? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Computation of cost valid? | No (Computed 516) | Yes | Yes |

| Total Path Cost | 493 | 341 | 291 (Optimal) |

The Zero Shot approach identified a feasible solution but failed to maintain calculation integrity. The CoT approach successfully computed the correct final cost but failed to reach the optimal solution. Only the Agentic System successfully identified the optimal solution and provided the correct cost computations. We also observed that CoT is highly sensitive to prompt design, whereas agentic systems provide a more robust (less sensible to the specific prompts used) path by decoupling exploration from computational logic.

Conclusion

At a high level, reasoning could be decomposed into two distinct aspects: a creative "exploration" component and a component dedicated to mathematical accuracy and logic. Agentic systems provide a robust framework for integrating these two elements to enhance overall reasoning capabilities.

Under this hybrid model, multiple LLMs can navigate high-level strategy and intuition, while a deterministic system handles rigorous computations and memory or state management. This separation directly addresses the issue of context decay and also has the benefit to create a system that is both auditable and transparent.

Beyond simple optimization, this model facilitates the development of systems capable of complex, multi-step reasoning. At Sabr Research, we are currently developing new architectural designs for agentic systems to further enhance these reasoning capabilities, ultimately enabling more robust systems for decision-support.